I have certainly been accused, in my life, of not liking science fiction very much. That's a partly fair assessment based on the fact that I don't think very much of the most famous sci-fi franchises. The cloying Star Trek mostly rings hollow to me because in my perception all its characters are merely types; Star Wars is a childish practice in technical complexity with no logic; and The Matrix is fake Kung Fu masquerading as pop philosophy. These are some of the first things one thinks of when one thinks "sci-fi", which is a pity because Terminator, Blade Runner, Battlestar Galactica, and many other works manage to do quite a lot with what is essentially fantasy fiction---a universe with its own rules and none of the baggage of human history. If this genre ever manages any truth, it's when humanity, as it is, is nonetheless echoed in the work, despite the universe it exists in bearing no resemblance to our own.

With that disclaimer out of the way, I come now to Mass Effect.

Mass Effect is a series of 3 video games set in the distant future where humans have managed interstellar travel. This connects humanity with several other sentient species who have a nominal unified government. In Mass Effect, the threat of galaxy-wide extinction is revealed in the form of sentient robotic beings known as Reapers. The entire series revolves around one person, Commander Shepard, who must confront these beings and save all sentient life in the galaxy from violent and horrible extinction. Mass Effect has Shepard grasping to understand the threat. Mass Effect 2 is Shepard building a team to combat the Reapers, while stemming their attempt at preliminary strikes on humanity, and Mass Effect 3 is the actual war between the galaxy and the Reapers.

However, the key point to the series is player choice and agency. The series has left several choices open, including the gender of the protagonist (both male and female have full voice acting), his birth place, his sexual orientation, his temperament, and his decisions in various difficult situations. Shepard is given the choice of saving entire species of potentially dangerous aliens or letting them die (this happens four times that I can think of). He can blow up unethical experimental labs based on personal principles, or he can be a pragmatist and salvage the facilities despite their being abominations. Shepard can take a lover, of either gender and of several species. And some characters are even expendable, with the story coming after their deaths being adjusted so that things play out differently because of those events.

The first question we must ask, when trying to assess how good something is, would be "is this a work of art or is it a product?". Of course, most things lie somewhere in between. But herein I am going to argue that either way you view it, Mass Effect 3 is a bad game. Just how bad is determined by which view you take. If it's a product it's miserable, and if it's art it's still fairly dreadful. The argument from many people has been "well, it's a good game up until that." They are wrong. This game is tragically cynical in its writing decisions, maladroit on the impetus for the events in the game, and entirely disingenuous about its ending.

The ending

It is important that the ending that has generated such controversy be described to the reader before proceeding. This is the only spoiler alert I will give. If you appreciate art and believe Mass Effect is art, my guess is that you don't care too much about the ending being "spoiled", or at least I hope you don't. Alternatively, you are someone who is amenable to the idea that Mass Effect is a product, in which case you must be duly warned about the ending.

At the beginning of Mass Effect 3, Earth is attacked by the Reapers. It's made clear that there is no hope to win. Shepard flees Earth in the Normandy to plea for help from the other species in the galaxy, and to try to unite them to fight. Shepard then spends almost the entirety of the rest of the game building war assets to help in this fight. The key asset is a device that has only recently come to our attention called The Crucible. The Crucible is a gigantic space gun ... capable of killing all Reapers everywhere and harming nothing else. Ok, fine, whatever, let's go with that.

Now, regardless of how many war assets you rally, the following will happen. The crew brings whatever conventional forces they have mustered to Earth to fight the Reaper invasion. Shepard and mates land and have a big fight with tons of enemies. Their goal is to reach a transportation beam in London that the Reapers have constructed which happens to lead directly to the control center of a nearby space station. That station happens to be the very one needed to activate the Crucible and destroy the Reapers.

Shepard and his teammates run toward the transporter beam, but are cut down by a Reaper laser beam. We hear a voice over the radio say everyone died. The Reaper walks away. Shepard gets up, badly injured, his armor destroyed by the laser, still holding his pistol, and runs toward the light. This transports him to the heart of the space station, among piles of dead bodies. He walks over a bridge to the control console for the giant space gun. His old commander (Anderson) is there too, and so is his nemesis (whose name is TIM).

Anderson and Shepard argue with TIM for a good while. Something takes control of Shepard's body and makes him shoot Anderson in the stomach. Depending on the ensuing conversation, TIM either shoots himself or is killed by Shepard. Anderson and Shepard sit down and chat a little, then Anderson dies from his wound. Shepard then realizes he has also been shot.

I want to assure you that the proceeding paragraphs are not made up.

Shepard crawls to the console in front of him and opens the station arms, allowing the Crucible to be used. The floor below him turns into an elevator (?) and lifts him up to a part of the station we've never seen before. Awaiting him is a holographic projection of a human child. The likeness is that of a child Shepard saw killed earlier in the game. This character is termed "The God Child" by the fans.

God Child goes on a wild rampage of illogical exposition. He says that the Reapers are not, in fact, sentient beings who decided to kill all advanced life, but are instead his invention and under his control. He reasons that advanced civilizations will always end up killing themselves by inventing synthetic life (robots) that turns on them. Thus, he created an army that allowed the civilizations to rise, and then came in and killed everyone right before they were to develop thinking robots. This cycle of development and extinction has repeated countless times, about every 50,000 years. Each time, the Reapers left behind primitive sentient life, who are free to be fruitful and multiply until the Reapers are sent around the next time to murder every last one of them.

Almost nothing here was foreshadowed. Shepard has conversations with Reapers themselves, who say that the extinction events are incomprehensible by human minds. No indication has ever been given that they operate under the control of anyone. There are numerous damning inconsistencies in this, which I will discuss later. So, to sum up the conversation, God Child says it was him all along, not the Reapers (who are just his tools). We do not learn anything about who the hell God Child is, how he was capable of such an extravagant plot, what his motivations are, or even whether he is still alive or not.

With the plot arc thoroughly maimed, the God Child completes his rampage by telling Shepard that because he has discovered the secret, the cycle must end. God Child presents Shepard with three choices. In each of these scenarios there is a bright ring of what I will call, for lack of a better name, phlogiston, that emanates from the Crucible to the entire galaxy. It could also be called space magic. The color of phlogiston is affected by the choice made. These are the options:

- Shepard can grab these two lightening bolt things. By doing this, he controls the Reapers and can make them stop attacking and bugger off. He is disintegrated when he does this. I don't know how he keeps controlling them if he disintegrates. The Crucible sends out a ring of blue phlogiston that destroys all the intergalactic traveling capabilities in the galaxy.

- Shepard can shoot a pipe. If he does this, the Crucible sends out a ring of red phlogiston that destroys the Reapers, and also destroys all the intergalactic traveling capabilities in the galaxy. The ring also destroys one of your good friends and an entire race of peaceful synthetic beings that you helped. The station collapses and Shepard dies.

- Shepard can jump into a hole. If he does this, he is disintegrated. The Crucible sends out a ring of green phlogiston that changes all robots in the galaxy into partially organic robots, changes all organic life to have electronics in it and become robotic, and destroys all the intergalactic traveling capabilities in the galaxy.

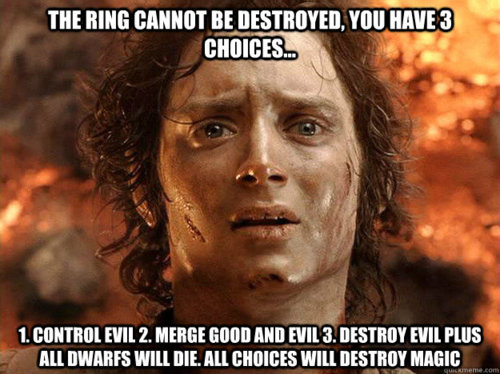

If the ending of Lord of the Rings was written by Bioware.

Note that the third choice is only available if you did a significant amount of work: doing side missions and buildings up a huge amount of war assets, plus playing the multiplayer portion of the game (for no discernible fucking reason).

With the options described, Shepard must choose. He will not ask the God Child any questions. He does not seek clarification. He does not attempt to contact the fleet to tell them some shit is going down and they might want to jump back to their homes. He does not send a "goodbye" message. He picks one and dies.

The Normandy, which was in the space fight orbiting Earth, suddenly bugs out and engages its faster-than-light engines just ahead of the phlogiston ring. At some point they took the time to go pick up the other crewmates who were on the ground when the Reaper laser beam fired. All of Shepard's comrades crash land on a desert planet. Fade to black.

(You can view the ending here.)

Mass Effect as a romance novel

My personal opinion is that Mass Effect is a product. It offers a vivid, but calculated, escapism to its consumers. To explain why I think this, we must discuss the payment plan.

The first game, while mostly self-contained, had an add-on pack Bring Down The Sky that took place after the events of the first game. This wasn't so bad. The pack could be played or not, took place after the game ended, but didn't bridge the story between the two games. I can't recall any reference to the events of the add-on anywhere in ME2 or ME3. No problem.

Mass Effect 2, on the other hand, had a bonanza of content that the buyer did not get upon initial purchase. This included adding a key character from the first game, Liara, into the game, for the low low price of $10. Liara, not coincidentally, was the primary love interest for many if not most of the players of Mass Effect. Her position in the second game materially affects the story of both Mass Effect 2 and Mass Effect 3. To be perfectly clear, a major character that almost everybody who played the first game liked was walled off behind a toll booth. "Oh, you expected this character you liked to be in the game? Ok, we can do that, but first let me ask you something: what's it worth to you?"

Shepard, don't you love me? It's only 15% extra.

Who could deny that this was, at this point, an economic endeavor primarily, and not a work of art? Imagine if a book came with extra chapters for a small fee. Imagine if Orwell was to omit the scene between Winston and Julia luxuriating in coffee after the consummation of one of their trysts. After all, the scene doesn't really change much, does it? Well, we can get you an estimate if you're serious about these characters! Hang on, I'll get a pen.

Here's the thing: either Liara was an integral part of the narrative of the second game or she wasn't. If that's an artistic choice, then you either leave her out or include her. But if you can be persuaded to add her in for a fee, isn't that just commerce?

But Bioware wasn't finished there. Two other characters, Kasumi and Zaeed, were also not part of your team without an extra fee. Because these team members contribute to the fighting in the end stage, they materially impact the ending that the player gets at the end of ME2, their actions have consequences in the third game depending on what happens, and they add depth to several elements of the game world. Finally, the Overlord package added two characters who both appear in the third game, but of course only if you paid earlier. One of these affects a part of how the final game plays out (more on this later).

These four paid downloadable content (DLC) packages that add, not meaningless equipment, free-play levels, or armor, but actual story and depth are clearly hallmarks of a product. There is no artistic integrity at stake because there is no artistic integrity.

The amazing thing here is that there was some art that went into this project. Though the inclusion of Liara in DLC was cynical, her character was vividly drawn by the writers, wonderfully voice acted, and clearly something that was worth a bit of extra green. There was never any doubt in my mind that I would buy the pack. The game was fun, she was interesting, no way I would miss out on that. Mass Effect 2 was an entertaining product that gave me what I wanted, without any kind of illusions of high concept. That is perfectly fine. But is it art? Not any more or less than what you get from Danielle Steel. It's escapism, it's entertainment, and it's interactive fun with a "choose your own adventure" element. Most of all, it can hardly be seen to be the product of a single voice or author who yearns to evoke something.

Come one, come all

The fact is that Mass Effect 3 essentially treats Mass Effect 2 as having been optional.

In Mass Effect 2, Shepard assembles a team of soldiers to fight a proxy battle between humanity and the Reapers. He recruits 12 people, all of whom accompany him on a "suicide mission" to a secret base. They emerge victorious, but members of the crew can (and usually will) die. Shepard can start a romantic relationship with three (I believe) of them. Because this game is incredibly open ended, the writers had to make sure that nothing that happened in ME2 matters for the third game. If you started a relationship with Miranda, then tough shit because she is barely in this game. In fact, while all of the characters from ME2 can appear in ME3, they are all in ancillary roles or at most the focus of a vignette, upon which they disappear and become just another mark on the "war assets" summary board.

From a business standpoint, this strategy makes perfect sense. You don't want to exclude those who didn't play ME2 from buying ME3. You especially don't want to exclude those people who didn't buy the extra DLC from buying ME3, nor the ones who got a bad outcome (Shepard can actually die at the end of ME2). However, from an artistic standpoint it is ridiculous. As a genuinely artistically successful series, can you imagine if the events of The Return of the King had to be written so that you could watch it even if you didn't see The Two Towers? This would not be credible. By making the series episodic they staked out a clear spot, and that spot is in a marketplace rather than a gallery.

It seems to me cognitive dissonance for Bioware to proclaim that their works are art, in the sense that a book or movie can be a work of art, the product of an author. If this is so, then why have they frequently stated that they use customer feedback to alter their games? Initially, a character (Tali) was not going to be included as a team member in ME3. Fan outcry on the Bioware forums convinced the developers to add her back. They changed the mechanics considerably from one game to the next because of complaints.

Failure as a product

If Mass Effect is a peculiarly addictive form of escapism, then how does Mass Effect 3 further the money-making, fan-pleasing endeavor?

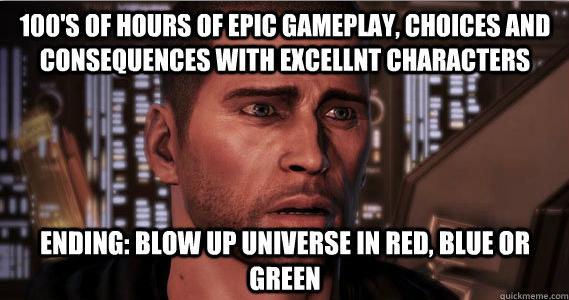

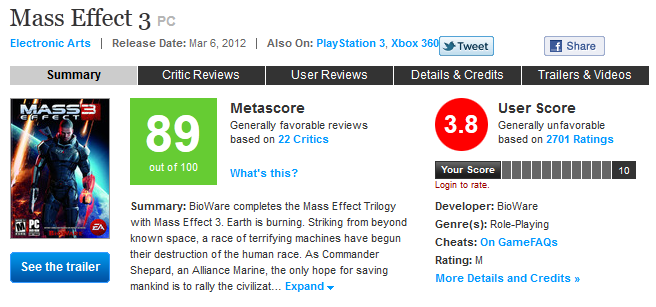

Abysmally. Upon release, the game drew widespread "critical" acclaim, meaning that the completely self-interested enthusiast press gushed. Dozens of simpering reviewers raved about the game, saying it was completely satisfactory and brilliant. The game garnered an 89 on Metacritic, a widely-used metric on critical success.

But tellingly, the user score for the game is a mere 3.8/10, and has 2 stars on Amazon.com. The fans were so displeased that they formed an international protest. Retake Mass Effect, a group who are said to have spearheaded this, formed a charity event to raise money and awareness of their displeasure. The Bioware forums blew up with scads of consumers pleading for Bioware to redo the ending. This wasn't a few cheezed off emo-kids: this was the base consumers of the game, the people who tend to buy DLC. People were saying that the ending was so poorly conceived, poorly executed, and divorced from the rest of the series, that they no longer wanted to play the previous games. The final enemy in the game jokingly became a hero, as fans said he was the last thing trying to save the fans from the ending.

The disparity between the Metacritic score and the User Score is a good sign of some major buyer's remorse.

Bioware was left, apparently, reeling. (I don't quite know why. To paraphrase Jack Shafer, when you leave a turd in the punch bowl, you normally expect your guests to gag.) Here they were, days after the release of the final installment of their crowning achievement, ready to crank out tons of new DLC and rake in even more cash, and all of a sudden a very large percentage of their market says "we are so disappointed that we retroactively re-evaluated the series". Bioware now say that though they will not change the ending, they are going to produce a new epilogue to the game---and moreover, it's free of charge. Companies do not make new content for their games free of charge unless they know they have a major problem.

However, I would contend that an artist would not make new material for the ending of his work, not for free or for pay, for any artistic reason. Of course, there have been notable examples of legitimate artists changing their material after publication. One such example is Ridley Scott's alteration of Blade Runner for the home video releases. Among other things, Scott removed the voice-over that was included in the theatrical release, and some deleted scenes were restored; however, many of these changes put the film back into the form of Scott's original working cut, which the studio wanted changed due to negative test-audience reaction. Peter Jackson's releases of the Lord of The Rings films on DVD include many scenes that were deleted due to time constraints of the theatrical format. In both of these cases, the author was putting the work back into the form he originally wanted---not adding scenes because of audience outcry.

Mass Effect 3 as art

Now, rather than the case above, we could choose to evaluate Mass Effect 3 as a real work of art. I would argue that this case is much, much worse for the game. One would inevitably come to the realization that as a piece of fiction it has a plot that makes no sense whatsoever and even within that nonsense story has numerous glaring holes. Adding insult to injury, it features insipid characters who don't act logically. Finally, the game is, at its heart, sci-fi pastiche.

Nothing that anybody does makes any sense

At the outset we see Shepard, a soldier who has been stripped of his rank, brought before three top military leaders. They tell him that the Reaper fleet is nearly upon them, and want to know what they should do. This entire scene, the first of the entire game, is absurd and pandering. The writers think to themselves that they need a way to vindicate Shepard in human eyes and portray him as the last hope for humans. But, and this is a general rule, as soon as a scene serves as one of a writer's bullet points, it usually ceases to have any reason to exist. Why would the leaders of the entire human army bring a guy who shoots things for a living into a boardroom 5 minutes before the enemy fleet arrives and ask him what to do? Wouldn't they be looking for a tactician? Someone experienced in ship-to-ship combat? Shouldn't they be moving to a secure bunker? Launch a nuclear strike? In other words, almost anything makes more sense than this scene.

As the writers go down their list, they want to set up the Earth to be in danger of complete extinction, but also leave time for the events of the game. So the Reapers simply land a bunch of ships, ground troops, and small artillery, and attack the planet building-by-building. Why? Why would this be the case? If the Reapers want to wipe out all life on the planet, they can do that easily. Hell, if the US in the 1950s decided to wipe out all life from the Earth, they could have done it easily. Why, instead, do the Reapers screw around with landing their large ships in the cities and picking off individuals with laser beams?

This is precisely the same question I always had with the opening scene of one of the most overrated movies of all time, The Empire Strikes Back. The Empire has discovered that Hoth is host to a rebel base. They arrive there with a star destroyer. Then, instead of just bombarding it from space, destroying it in a matter of seconds, they proceed to land vulnerable walking tanks onto the snowy surface. No idiot in the world would do this. It's totally baffling as a scene unless you acknowledge that the writer simply wanted to have a scene where ships wrap up the walkers in tow lines and trip them. That's it. Somebody wanted giant walking tanks because "ooh, that would be cool".

The next thing Shepard does upon leaving Earth is to pop over to Mars and pick up his old friend/old flame Liara. Liara, we're told, has been working on deciphering the plans of a war machine, the Crucible, that can destroy all Reapers. I have questions. 1. If the high-command knew of this then they should have known to take the Reaper threat seriously, move the plans to a secret location, tell everyone else about it so they could get help, and get to work on it before the Reapers got there, right? 2. The existence of the Crucible, a device built by the Protheans to destroy the Reapers, proves that the Reapers are real. Wouldn't that have been extremely helpful in convincing the unified alien government of the threat? 3. Would they really invite Liara, an alien who was a known information broker, to be the person in charge of this military project? They state themselves that the designs were simple enough that anybody could build it. Why would they want a non-engineer to help them build something that they don't need help building? Or was this just a way to make sure Liara was a central character?

At this point, roughly 30-45 minutes into the game, we've been presented only with things that make no real sense. Not "make no sense" in a surreal, subjective, ethereal, artistic, or existential sense, but in a "this is not internally consistent and everyone is acting like a moron" sense. The events are essentially prevarications in service of a lazy script writer who knows he wants to get from point A to point B, regardless of whether in his plotting there is any plausible narrative thread.

There are two main villains for no reason

Upon reaching Mars, Shepard has to contend with, not Reapers, but a group of human supremacists called Cerberus. Mere months earlier, Cerberus employed Shepard to help save human colonies from Reapers. In other words, they were perhaps a well-funded group, but nothing on the level of a government army. But suddenly they have a gigantic military presence and pose almost the same threat to the building of the Crucible as the Reapers themselves. We are thus presented with two separate enemies, which alternate throughout the levels of the game.

There's one slight issue with this. Why would a group of human supremacists hinder the building of a machine that saves Earth? The game gives us the justification that their leader, TIM (which stands for The Illusive Man, I shit you not) wants to take control of the Reapers, rather than kill them, so that he can study their technology. By building the Crucible, this will ... what? How does building the Crucible in any way affect this plan? Cerberus is already in possession of a dead Reaper, and they could be in possession of tons of salvageable technology once the Crucible is deployed. TIM would rather they be allowed to continue ravaging Earth so that he can, I suppose, trap a few of these things alive? This could work, except for the slight issue that he has absolutely no plausible plan for controlling the Reapers.

The writers were aware of these problems, so they tell us that TIM has been "indoctrinated". This is a way of saying that the Reapers have brainwashed TIM into doing what they actually want him to do, which is hinder Shepard's ability to build and deploy the Crucible. Therefore, he doesn't act rationally. This is the literary trope that cures all narrative ailments, isn't it? Ok, let's say this is true. When did it happen? Was TIM under Reaper control when he gave Shepard the resources to utterly destroy the Reaper base in Mass Effect 2, only months prior to the events of Mass Effect 3? So it happened in the intervening months?

Here's another question: why? Cerberus was not a particularly powerful organization prior to this. Why indoctrinate TIM? Why not any one of dozens of significantly more important people, such as military leaders, politicians, or power brokers? After all, one of them would have been included in the construction of the Crucible, and therefore know its secret location. This would allow the Reapers to just go there and blow it up, totally ensuring their victory beyond all doubt. Because TIM was an avowed enemy of the Alliance, he was possibly the worst choice to indoctrinate.

Is the inclusion of Cerberus really in service of art? By having two sets of enemies, the designers made sure that there was some variety to the gameplay. You fought humans and then you fought Reapers. In any normal world, where this is a game meant for fun, that would be acceptable. But when you assert that you have immunity from customer satisfaction because you are making art, that becomes as damning as including Jar-Jar Binks in a movie to sell children's toys.

People die for effect

As stated earlier, all characters that survive Mass Effect 2 appear in this game. This is usually in an "episode", of sorts. It's either part of a mission, or a little side mission of its own. Since it's a war, you would assume that some of these characters will die, and die some of them do.

However, the reason for their deaths is peculiarly pointless. It's peculiar because neither of them die the pointless deaths that accompany any war. They die specifically to evoke emotion, and always with a ton of fanfare. This is not how war works.

The first certain death that I encountered was Mordin. After accompanying him to an elevator that leads to a mechanism that will spread a cure to a disease (the Genophage, which makes 99.9% of people on the planet infertile), he states that the tower is booby trapped to explode if it's used to distribute a cure. Leaving aside the technical issues here (he could override the explosion, but only until he did what it was specifically designed to prevent?), this is just not good writing. A fan wrote on the Gamespot messageboard "If you're going to kill important characters, his [sic] final moments must be their most epic." This is stupid and wrong. People die in war because of bullshit. A random bullet, a land mine, a crashed helicopter, friendly fire, disease, a mortar from nowhere. When you make the death of a character an event it's called "fan service". It's manipulative piffle; I half expected a treacly piano accompaniment.

The second such certain death is similar in purpose, but even less plausible in execution. It's well established that the robotic creatures, called Geth, are computers the way we think of them: all data transfer is a copy. But we are told that Legion, a Geth we know, has to die so that his mind can be given over to the rest of the Geth. Why? What would lead us to believe that the copying of some data would lead to the death of the creature it was copied from? His sacrifice means nothing because it is counter-logical.

The common thread here is that during a war of humongous scale, characters only die for reasons totally apart from the war itself, and for "important" reasons. Doesn't that seem rather incongruent? Moreover, the writers make sure to "prepare" us for the death, tell us exactly why it's happening (although neither reason holds water for me), and to say our goodbyes. This is fundamentally dishonest fantasy tripe, worthy of perhaps a children's novel.

The ending is indefensible

There are three reasons that the ending is peerlessly horrible. The first is that it wraps the story up by just making up a bunch of new rules (this is a sin). Second is that those rules themselves don't hold up to the barest of thought processes. The third is that the whole segment is poorly written, as it's a complete break in tone and the principal characters become brain dead.

I turn now to the obligatory haranguing of the writers on the grounds that their ending contains plot holes. This is an undignified topic, and I don't relish taking it up. This discussion is in no way complete, and is only about major things. Readers are referred to a much more detailed discussion here. The ending scenes can be viewed here.

The transporter and breaking the prime rule of story telling

Shepard needs to board the space station near Earth to deploy the Crucible, but the Reapers have full control of the station and have made it inaccessible. The Crucible can kill all Reapers. Because allowing Shepard up to the station will mean their doom, the Reapers would obviously do anything to keep it inaccessible. Rather than do this, they instead create a doorway straight into the very-well-defended station in the form of a transporter beam. This beam takes anyone who goes into one end (which is in London) to the station. They put a large force on the ground to defend the beam, and it sure looks like they succeed. We see all the troops heading to it wiped out, including Shepard and his teammates. But Shepard wasn't killed, merely knocked out. When he awakens, we hear the radio say everyone died, and we see the big daddy Reaper named Harbinger fly away.

Why does this beam exist? The space station has no bearing on the destruction of Earth, which was well on its way to completion. The station, in fact, did not even reside near Earth until the Reapers moved it there. Why move the station into the way of the unified military fleet and create a back door right into it? We are never told what it could possibly be for. When we arrive on the other end, there are piles of dead bodies, but those bodies are presumably dead people from when the Reapers seized the station. In any case, why would they be collecting dead human bodies from Earth? And even if they were collecting the bodies, the space station wouldn't be part of that plan because only near the very end did they decide to move it to Earth.

Why would Harbinger fly away after he thought Shepard died? Regardless of whether Shepard was really dead (and apparently super advanced beings don't check for a pulse), this was a highly vulnerable and important thing to defend. But Harbinger traipses away and leaves it undefended?

This was meant to be a climactic tension-building scene ending in a devastating loss of life. But it isn't, because the events that arranged for the scene are absurd. Moreover, it's incredibly contrived: Shepard has to make it to the station to deploy the Crucible because that's what the writers wanted to do. Ok, then don't have a scene where everyone dies beyond all reasonable doubt and the victorious party implausibly walks away.

These scenes break, in several ways, a key rule of storytelling in any genre, but especially sci-fi: the events depicted can be impossible but they should not ever be wildly improbable. That is, it's ok to have a scene where our hero encounters a futuristic fictional anti-matter bomb, but it's not ok to have that hero then randomly guess the 7 digit code that disarms it. The bomb is impossible, but the guessing of the code is possible, just totally implausible.

The writers of Mass Effect 3 show wanton disregard for this rule. We're asked to accept that there are incredibly powerful laser death rays. Fine. But you expect us to believe that the beam randomly grazed Shepard? That Harbinger wouldn't check if we were dead? That they would be using this weapon rather than just turn off the transporter beam? It's ridiculous.

From the morgue to the control center

After waking from unconsciousness following Harbinger's laser death ray, Shepard pulls his injured body up and hobbles into the transporter beam, armed with his pistol. The transporter takes him to a place on the space station with a lot of dead bodies, and again renders him unconscious. He awakens after some time, looks around, and then over the radio he hears Anderson. Anderson says that he is also on the station ("I followed you up"), but that they must have arrived in different places. Shepard walks through a door, across a bridge, and arrives in the critically important control room, from which it is believed the Crucible can be deployed. Anderson is already there at the console when you enter through the only apparent door into the room.

How could any of this possibly have happened? Anderson was not behind you when the death laser beam struck. If he came later, I have to ask, is Harbinger an idiot? He just let anybody else who came by to jump in the beam? If Anderson knew he came in after Shepard, then presumably he would have been visible to Harbinger. Are we expected to accept that the king Reaper just said "eh, good enough for government work."?

How could Anderson not have encountered Shepard on his way to the control room? Allowing that there's some voodoo whereby another door into the room existed but was simply obscured, why does this transporter beam go to multiple randomized locations that all are one short corridor away from a very important control room? It is not plausible that the Reapers would make such a thing.

A meeting with the Illusive Man

The next scene tries to reiterate a bunch of the "themes" of the game, and takes the form of a drawn out argument with TIM in the control room. At this point we're meant to believe that TIM is indoctrinated, and therefore mainly under the control of the Reapers, but still thinks he is autonomous.

TIM comes into the room with Anderson and Shepard, and says that he warned Shepard not to go down this path. Both men try to convince TIM that he is under Reaper control. During the course of the conversation, Shepard and Anderson both lose the ability to control their bodies, and we are led to believe that it is TIM that is controlling them. Shepard remarks that controlling a person like this is much easier than TIM's ambition of controlling all the Reapers. During the course of the argument, TIM makes Shepard shoot Anderson in the torso. The conversation between the 3 men continues unabated (I guess Anderson is a tough bastard). After a back and forth about the risk of using the Crucible to control the Reapers rather than using it to destroy them, either Shepard shoots TIM or TIM shoots himself after realizing his is indoctrinated.

It's a bit difficult to say where to begin with this scene. The writers are throwing in new things right at the end. How is TIM controlling human beings? These aren't robots, he isn't using some form of mind control that we know of. It was specifically stated (many times) that Shepard has no electronic components in his body to control him. This scene isn't opaque, it's just inconsistent. It's establishing new rules, new logic into the story; but you simply can't do that at the end. By making up new rules to advance the ending, you lose any internal consistency, and moreover you lose any dramatic tension, because the audience has no way of knowing the stakes of the conflict or of guessing how a character will behave. And what an artless way to do it! 10 minutes before the end of the game, you arrange for a drawn-out debate facilitated by mechanics that heretofore were either never mentioned or were specifically contradicted.

In a way, this scene is a metaphor for Mass Effect 3. The player, like Shepard, has control wrested from him, despite having been led to believe that such a thing would not happen. It is a dramatic shift in tone from the rest of the series, and the histrionics by the scene-chewing Martin Sheen certainly don't help. The conversation is pointless and the result is a large break in canon for no apparent narrative purpose, apart from drawing a parallel between TIM and the villain from Mass Effect, Saren (which is so belabored by this point that one might think Bioware thinks its players are brain dead).

Aside from this, it bears mentioning that the very premise is totally bogus. Why would TIM think the Crucible, which as far as we know is just a Reaper-seeking gun, was capable of controlling Reapers? He can present no evidence for this case, he makes no mention of any plausible function of the Crucible that could be made to do this. The entire argument over his proposed action is a bit undermined by the fact that nobody in his right mind would expect that the action is achievable.

The God Child

Shepard is lifted up to a large room, and a holographic projection of a child approaches him. Shepard asks if the child knows how to stop the Reapers, and the child replies that he controls the Reapers. They are his solution to the problem of sentient races making synthetic life that then wipes them out: "We harvest advanced civilizations, leaving the younger ones alone." By this he means that new Reapers are made out of the genetic material of the dead. He says that the fact that Shepard made it to him means that this solution will no longer work. He indicates that the Crucible makes possible destruction, control, or synthesis (those endings listed previously).

This scene is entirely crazy.

Who the hell is this person? How did he get there, where was he from, and why is he doing this? Why does he look like the kid Shepard saw earlier? Did he read Shepard's mind?

If the being controlling the Reapers was present on this space station, then all the events of Mass Effect would not have happened. In that game, the station was supposed to be the entry point for the Reapers from "dark space" (they needed a portal to get to the galaxy, and this was it). The humans stop the immediate Reaper invasion by keeping the portal closed and defeating the Reaper who stayed behind to open the door. So why the hell wouldn't God Child just open the damn door? He's on the fricken station and has been for thousands of years. Is he an idiot?

This also invalidates all the events of Mass Effect 2, because the premise there was that the Reapers were harvesting human colonies to make Reapers. But they never could have harvested all of the humans by going from one backwater planet to another over the course of years. Why would they bother with what they did in that game? From the size of the colonies, they must have harvested thousands of times the number of people per day when they descended on Earth.

The premise that the solution to the people-beget-killer-robots problem should be "kill all people" is incredibly odd. Wouldn't it make way more sense to kill the robots? Why would he think that always happens? These are self-aware robots, every bit as reasoning as an organic regular person. Not all of us want to commit genocide---in fact, I think rather a lot of us don't want that.

Why does Shepard making it upstairs mean that the solution will no longer "work"? The God Child is the only one who can deploy the Crucible, so he can just decline to let it be used, let the Reapers kill everyone, and finish this cycle like all the other ones. If he was willing to kill trillions of sentient people, then he is surely a fanatic, and would not give up his maniacal plan simply because some guy built a giant space gun that doesn't even work.

This scene is wrong. A writer may have wanted this to be the outcome, but the groundwork laid makes it impossible unless the child is a liar. Since he does activate the Crucible after you pick one of the space explosion choices, we can assume that he's not lying. This is narrative cheating in the first degree; it breaks all continuity and contradicts several important ideas that were presented as true.

To the latter point, I'm thinking principally of the assertion that all Reapers are under the control of someone and not sentient. The problem is that we had a drawn-out conversation with Sovereign, a Reaper, who explains that the Reapers are each their own nation, free-thinking, and carry out extinction for reasons that can not be explained to humans. Why would he say that? He has no reason to deceive Shepard. In fact, the reason can be explained in a simple sentence: we kill you so you won't make robots.

So bad that a crank theory makes more sense

Fans of the series, reasonably mortified by what they had just seen, turned to the internet to vent their anger. Soon enough, someone with a very inventive imagination and plenty of time to edit video on his hands produced the following video. I will summarize below.

Specifically because none of the events of the end of the game seem to match with any previously laid groundwork, the proponents of Indoctrination Theory posit that the entire endgame is in Shepard's mind as he lies unconscious on the street in London following Harbinger's attack (the developers have more or less said this is not the case). They say that he has been slowly indoctrinated by Reapers, and that this is the final stage in that process, in which he finally becomes their slave by choosing the "control" ending, ensuring that the Reapers live. If Shepard chooses, instead, to destroy the Reapers, then he is rejecting indoctrination, and will wake up. Their key pieces of evidence are

- TIM is able to control him, which is not possible

- Shepard develops a wound in exactly the place where he shot Anderson

- The God Child takes on a form that nobody but Shepard would know (the theory also asserts that the scenes near the beginning, where Shepard sees the child, are also not real and a product of an unreliable narrator)

- There is a scene at the very end of the game, if you chose the "destroy" ending, that shows Shepard draw breath, and he appears to be on the street in London. (This is actually the best point.)

- There appears to be some subtle clues, such as Reaper-noises during the scenes, when no Reapers are around, and the ghostly image of the child (seeing ghosts is a stated side effect of indoctrination)

- The vision of your crew escaping is not plausible

- Nothing makes any sense, just like in a dream.

Needless to say, I don't give this theory much credence. I think it's giving the writers an awful lot of credit to devise a way that they have given us a David Lynch type subjective scene that actually all makes perfect sense when you consider it. This is the end of the final game in the trilogy; when do you think the reveal was going to happen?

As stated before, the developers have essentially stated that this theory doesn't hold up (although I can't provide any evidence from the story for it not being true). However fantastical it may be, though, it sort of encapsulates the disappointment in and rejection of the story's conclusion by the audience---so bad that they would rather believe that the whole ending never really happened, and that the character is just in limbo.

For art, it's awfully familiar

Whatever originality the series had at its conception, it basically forsook in this installment.

The main point, given the ending, seems to be that robots kill their creators. This is new? This is precisely what The Matrix, The Terminator, and 2001: A Space Odyssey are about. And the Terminator movies did it far better in far less time. Those films actually see the issue from several points of view, they intertwine mother/son relationships, growing up and adulthood, even as they revolve around machines killing man. They admit the complexity of the issue. In Mass Effect, the treatment of the problem is so facile that it simply becomes a reason to build a space gun. What do we conclude about this theme from the events of the game, and especially the ending? Not damn much.

From a purely stylistic point of view, the final scene reminds one most of the ending to The Matrix Reloaded, in which Neo enters a strange room full of television screens and has an improbable conversation with someone called The Architect. That immediately leads one to the thought that The Matrix films also detailed a repeating cycle of extinction and rebuilding at the behest of a robotic overlord. The key difference, of course, is that the final scene of Reloaded was the only part of the movie that was interesting, whereas the scene at the end of Mass Effect 3 is a shit sandwich in an otherwise palatable war saga luncheon.

Agency lost

The game's ending does not substantively depend on what happened during the game, and even less so on the earlier games. The outcome is the same regardless of choices made during the series, despite the developers telling everyone to hang onto their save files to be imported. Did you save the Rachni species? Doesn't matter. Did you rescue the heads of state, or let them die? Seemed like that would change something, but it doesn't. The endings are essentially are the same but with a different color explosion.

There are only three ways that the ending depends on anything, and this is how many "war assets" you acquire, the game's way of monetizing your actions. One is that green space explosion is available if you have a high value. Another is that you get the 1 second clip of Shepard breathing if you had high assets and chose red space explosion. Finally, if your assets are very low then Earth will not be saved. War assets are extremely arbitrary, with seemingly significant actions taken being scored very low.

What do you have if you take Mass Effect and you remove the choice and agency? You have a mid-grade cover-based shooting game punctuated with short dialog sequences that are shown to mean nothing in the end. Some of those scenes feature good voice acting, a few compellingly drawn characters, but all of them feature very weird animation and questionable composition visually. In short, without choice you have a fair to mediocre series of games with a nearly featureless protagonist. When the ending throws away your choices, and you realize that the choices do not matter, then it makes sense that people are saying that Mass Effect 3 retroactively ruins the first games. That's imprecise: what it does is make you evaluate them apart from the choice, and the series doesn't benefit from such an evaluation.

BioWare, as I've mentioned, has said they are producing an epilogue to the game in the form of new scenes. These are supposed to provide closure for the characters. The ending will not be altered in any way. I highly doubt that these will have any impact on the quality of the product or the perception of that product.

One wonders what the point of the exercise was. Did BioWare really want to make a point that one's death is irrelevant to one's life, about the immediacy of our choices, Sartre meets Star Trek? If so, the employment of a deus ex machina to unify the outcomes makes it a rather clumsy attempt.

Regardless, what was expected to be a high-water-mark in interactive fiction is, I think, now widely held to be a low-point, with the parent company of Bioware, EA, being voted the worst company in the world on Consumerist. This is one case where the audience got it right.