In a gas such as the air you're breathing, not all of the molecules are flying around with the same speed. If they were, that would be pretty amazing. Nevertheless, most of the molecules are flying around at about the same speed. And the speed is related to the energy. We'd like to know what the average speed is, how many are going faster than that, and how many are going slower. To do that we first have to determine how much energy each of them has.

We already discussed that, for a gas at least, the average energy depends on the temperature. We obviously expect that the answer to both of the questions we just asked depends somehow on that.

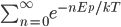

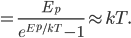

Here's the answer.

That's it. And yes, that

is the same

is the same  as in the ideal gas law,

as in the ideal gas law,  .

.  is called Boltzmann's constant.

is called Boltzmann's constant.

By the way, instead of using Joules, now that we've changed over to talking about the very small things, the unit of choice for energy is the "electron volt". 1 electron volt (abbreviated eV) is equal to a very tiny  joules. But since the particles we're talking about tend to have even smaller energies than that, this makes it convenient. In fact, for a particle to have even 1 eV of energy would be very unusual. Anyhow, you can look up

joules. But since the particles we're talking about tend to have even smaller energies than that, this makes it convenient. In fact, for a particle to have even 1 eV of energy would be very unusual. Anyhow, you can look up  and put in

and put in  K (which is room temperature) to see what

K (which is room temperature) to see what  is for room temperature. You'll find that

is for room temperature. You'll find that  is about 1/39 eV, or about 0.025 eV, which is a handy number to know.

is about 1/39 eV, or about 0.025 eV, which is a handy number to know.

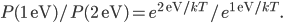

We can't immediately say what the probability of having energy  is. That's because for now all we know is a proportionality, and not an equality. But we can immediately say how much more probable having 1 eV of energy is than 2 eV of energy at temperature

is. That's because for now all we know is a proportionality, and not an equality. But we can immediately say how much more probable having 1 eV of energy is than 2 eV of energy at temperature  . It's

. It's

At room temperature

is about 1/39 eV, thus having 1 eV is about

is about 1/39 eV, thus having 1 eV is about  more likely than having 2 eV. Wow, that's a lot more likely! Having significantly more energy is very rare in a gas at room temperature. We would think, then, that the average energy of a particle in a gas at room temperature is probably much lower than that.

more likely than having 2 eV. Wow, that's a lot more likely! Having significantly more energy is very rare in a gas at room temperature. We would think, then, that the average energy of a particle in a gas at room temperature is probably much lower than that.

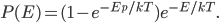

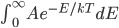

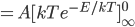

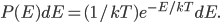

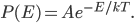

As always, to make a proportionality into an equation, we must find a constant. That is, the true probability of a molecule having energy  is

is

How can we find

? Well, the probability of being at any energy has to be 1. The sum of all probabilities is 1. Now, in principle, a particle can have any energy, from 0 to infinity, and all numbers in between. But for the moment, let's just simplify things and assume that energy comes only in packets. This is for a technical reason that I'd rather not discuss right now. We'll let each packet be 0.001 eV. (This isn't as unrealistic as you might think. In the end, energy really does come in packets.) So the particles can have 0 eV, or 0.001 eV, or 0.002 eV, etc., but they can't have 0.0005 eV.

? Well, the probability of being at any energy has to be 1. The sum of all probabilities is 1. Now, in principle, a particle can have any energy, from 0 to infinity, and all numbers in between. But for the moment, let's just simplify things and assume that energy comes only in packets. This is for a technical reason that I'd rather not discuss right now. We'll let each packet be 0.001 eV. (This isn't as unrealistic as you might think. In the end, energy really does come in packets.) So the particles can have 0 eV, or 0.001 eV, or 0.002 eV, etc., but they can't have 0.0005 eV.

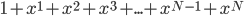

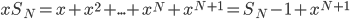

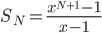

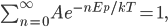

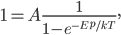

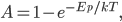

The sum of all probabilities can now be done pretty easily. I'll calculate it here, but feel free to skip.

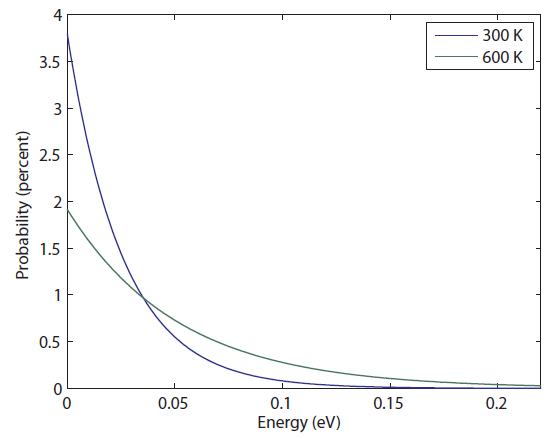

Let's take a look at what this means. The most probable energy, surprisingly, is zero. However, this does not mean having zero energy is probable! It only means it's more probable than having other energies. At 300 K, it's about a 3.8% chance. The probability of having 0.001 eV is 3.7%. But the probability gets really low really fast. Having just 0.01 eV is 2.6% and 0.05 eV is just 0.5%.

Here, I'll plot it for you:

But look what happens as the temperature goes up. For something at 600 K, the probability of having no energy decreases a lot, down to 2%, and the probability of having higher energy goes up. Whereas the probability of having 0.02 eV at 300 K was basically zero, at 600 K it's not. You have a 1 in 1000 chance of having that much energy if the gas you're in is at 600 K.

But look what happens as the temperature goes up. For something at 600 K, the probability of having no energy decreases a lot, down to 2%, and the probability of having higher energy goes up. Whereas the probability of having 0.02 eV at 300 K was basically zero, at 600 K it's not. You have a 1 in 1000 chance of having that much energy if the gas you're in is at 600 K.

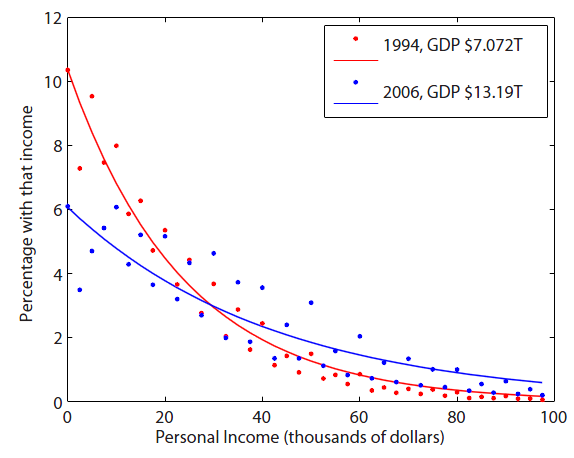

The analogous relationship is to what some citizen's likelihood of having a certain amount of income is. The first thing that matters is how rich the country you're in is. If the whole economy has a lot of wealth, then you stand a good chance of having more. But still, within any society, there are rich people and poor people. And there are always far more poor people than rich. So, here's the annual personal income in the US for 1994 and 2006:

This looks very much like the distribution for energy. In 1994 there were only roughly 7 trillion dollars to go around, so the probability of making only $2,500 in a year was decent. By 2006, the amount of dollars nearly doubled, even though the population only went up by about 10%. So the odds of only making only $2,500 annually dropped, and the odds of making $50,000 improved. 2006 is kind of at a higher "money temperature" than 1994 was, simply because of the combined wealth of the country (the total number of dollars that existed).(For more info as to why the US is Boltzmann distributed, see this page).

This looks very much like the distribution for energy. In 1994 there were only roughly 7 trillion dollars to go around, so the probability of making only $2,500 in a year was decent. By 2006, the amount of dollars nearly doubled, even though the population only went up by about 10%. So the odds of only making only $2,500 annually dropped, and the odds of making $50,000 improved. 2006 is kind of at a higher "money temperature" than 1994 was, simply because of the combined wealth of the country (the total number of dollars that existed).(For more info as to why the US is Boltzmann distributed, see this page).

Now, the thing we usually care about are things like what the percentage of people are poor (which is like asking how many particles have energy between 0 and 0.01 eV), or how many are rich (like how many particles have energy between 0.01 and 0.02 eV). That is, we want to know what proportion of particles there is within a range of energies. Fortunately, probabilities add. So if we want to know how many are going to have between 0.01 and 0.02 eV, you just have to take all the probabilities between those two numbers and add them together. And the answer is that at 300 K, 23% of the particles have energy between 0.01 and 0.02 eV.

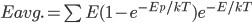

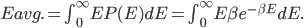

We also might care about some statistics. In the economy we might want the average income. In physics we might want to know the average energy. Well, we can do that pretty easily too. If 5 people make $20k and 10 people make $30k, then the average income is just  thousand. We didn't just average 20 and 30; we weighted each value by how many people made that much. Another way to say this is that the average is the sum of the percentage of people making that much times the amount they made,

thousand. We didn't just average 20 and 30; we weighted each value by how many people made that much. Another way to say this is that the average is the sum of the percentage of people making that much times the amount they made,  . So, the average energy of a particle in a system with temperature

. So, the average energy of a particle in a system with temperature  is the sum of

is the sum of  for each

for each  from 0 to infinity.

from 0 to infinity.

Simple, right?

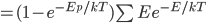

Of course, actually doing the sum is a bit challenging.

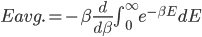

At room temperature, the average energy is 0.0251 eV. That's actually very close to

, which is 0.0256 eV. So if you want to know what the average energy is, all you have to do is calculate

, which is 0.0256 eV. So if you want to know what the average energy is, all you have to do is calculate  . (The error is from the fact that we divided energy into packets that were too big.)

. (The error is from the fact that we divided energy into packets that were too big.)

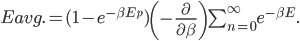

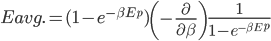

Now I'm going to calculate the true average energy, and it won't include anything about the packets. However, the mathematics is more complicated, so all but the most technical normals should not think about reading this.

"Wait just a damn minute", you might say. "Are you trying to tell me that if I have a gas that's at an extremely high temperature, and I pick an atom at random and check its energy, the most likely outcome is that it has no energy?! It was standing still?!" After all, the biggest probability is clearly when

. The answer, of course, is "no!" There is more to it than this, and we'll pick up here next time. But keep in mind that what we're saying is that the probability of having energy

. The answer, of course, is "no!" There is more to it than this, and we'll pick up here next time. But keep in mind that what we're saying is that the probability of having energy  at temperature

at temperature  goes like

goes like  .

.